The surge in earthquakes shaking Oklahoma, Texas and other parts of the nation’s mid-section are likely caused by million of gallons of toxic oil and gas wastewater being disposed of underground, two new studies have found.

Scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder and the United States Geological Survey analyzed data from earthquakes and more than 106,000 active injection wells across the central and eastern part of the nation, the largest such study to date. They found that “the entire increase in the number of earthquakes in the U.S. midcontinent is associated with injection wells,” according to Matthew Weingarten, a doctoral candidate at the university who led the study.

Weingarten and his colleagues also discovered that wells blasting the most wastewater into the ground, and at a faster rate—more than 300,000 barrels a month—were more likely to be linked to earthquakes. Their research was published Thursday in the journal Science.

Similarly, two geologists at Stanford University discovered that greater seismicity in certain counties in Oklahoma was often preceded by 5- to 10-fold increases in the volume of wastewater injected. Their findings were published Thursday in the journal Science Advances.

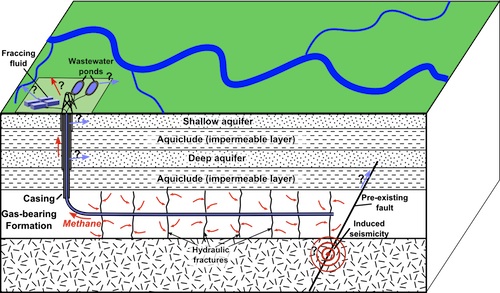

These two papers, the latest in a series of studies on the issue, add to the growing consensus among scientists that the spike in mid-U.S. earthquakes is man-made––and the oil and gas industry is to blame. Conventional oil and gas production has always generated wastewater, but the boom in unconventional fracking, a method to extract previously elusive oil and gas reserves, has led to the production of much more water that needs to be injected below the surface, prompting disposal in seismic-prone areas.

In Oklahoma and Texas, oil production has nearly doubled and tripled, respectively, between 2009––the year when earthquake numbers started escalating––and 2014. For both states, natural gas production also significantly increased during this time.

Energy companies say there’s no proven link between earthquakes and the waste disposal procedures associated with fracked wells.

During the oil and gas production process, drillers produce two main types of wastewater. There’s “flowback,” chemical-laced water used to frack a well, which comes up mostly before production begins. Then there’s “produced water,” the naturally occurring water that flows up a well during production. Both types can end up down a disposal or enhanced oil recovery well.

Not all of this wastewater ends up being injected underground, however. Some states, such as Pennsylvania, might treat the waste and store it in tanks or open-air ponds or recycle it for use at another drilling site, or other purposes. But in Oklahoma and Texas, injection is a major form of disposal.