Policy intellectuals — eggheads presuming to instruct the mere mortals who actually run for office — are a blight on the republic. Like some invasive species, they infest present-day Washington, where their presence strangles common sense and has brought to the verge of extinction the simple ability to perceive reality. A benign appearance — well-dressed types testifying before Congress, pontificating in print and on TV, or even filling key positions in the executive branch — belies a malign impact. They are like Asian carp let loose in the Great Lakes.

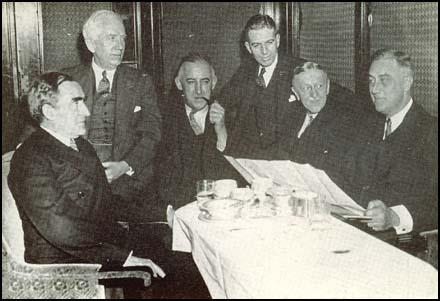

It all began innocently enough. Back in 1933, with the country in the throes of the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt first imported a handful of eager academics to join the ranks of his New Deal. An unprecedented economic crisis required some fresh thinking, FDR believed. Whether the contributions of this “Brains Trust” made a positive impact or served to retard economic recovery (or ended up being a wash) remains a subject for debate even today. At the very least, however, the arrival of Adolph Berle, Raymond Moley, Rexford Tugwell, and others elevated Washington’s bourbon-and-cigars social scene. As bona fide members of the intelligentsia, they possessed a sort of cachet.

Then came World War II, followed in short order by the onset of the Cold War. These events brought to Washington a second wave of deep thinkers, their agenda now focused on “national security.” This eminently elastic concept — more properly, “national insecurity” — encompassed just about anything related to preparing for, fighting, or surviving wars, including economics, technology, weapons design, decision-making, the structure of the armed forces, and other matters said to be of vital importance to the nation’s survival. National insecurity became, and remains today, the policy world’s equivalent of the gift that just keeps on giving.

People who specialized in thinking about national insecurity came to be known as “defense intellectuals.” Pioneers in this endeavor back in the 1950s were as likely to collect their paychecks from think tanks like the prototypical RAND Corporation as from more traditional academic institutions. Their ranks included creepy figures like Herman Kahn, who took pride in “thinking about the unthinkable,” and Albert Wohlstetter, who tutored Washington in the complexities of maintaining “the delicate balance of terror.”