Nearly 60 years ago, Herbert Matthews of The New York Times interviewed a rebel-with-a-cause most people thought was dead. Matthews’ scoop in the tangled jungle of Cuba’s Sierra Maestra proved that the man was alive. His name (which in its entirety was but four syllables) would soon come to be known the world over. To his followers, the first two syllables would suffice: “Fi-del.”

Castro’s quest to topple Cuban strongman Fulgencio Batista captured the imagination of millions. Victory, secured after only two years of urban insurrection and guerrilla warfare, catapulted the 32-year-old former lawyer and son of a wealthy landowner into the ranks of revolutionary stardom. After the catastrophes and crimes that had befallen the 1917 Bolshevik project, Castro seemed at first to herald something new. His was the first socialist revolution, after all, to have been made without the central participation of the Communist Party (and even, it appeared, against the party: In the aftermath of Castro’s failed attack on the military barracks of Moncada in Santiago de Cuba on July 26, 1953, the party’s apparatchiks had denounced him as a “putschist” and an “adventurist”). All previous socialist revolutionaries had seemed grimly puritanical. By contrast, Castro’s barbudos appeared almost to be bohemians with guns. Democracy and radical reform were poised to replace dictatorship and social misery.

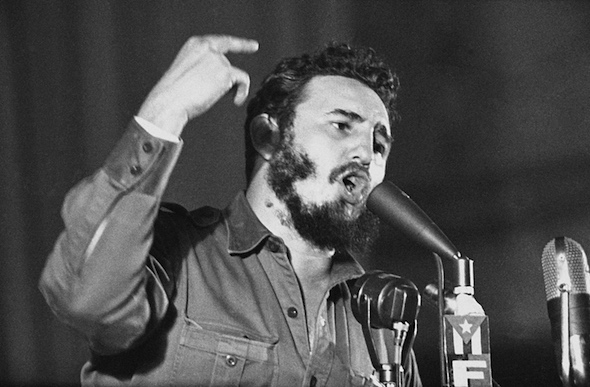

The hundreds of photographs taken of Castro and his men as they made their 500-mile victory march up the Central Highway from Santiago de Cuba to Havana capture something of the country’s exhilaration and popular acclaim. Burt Glinn, for one, an intrepid 33-year-old member of the New York office of the Magnum Photographic Cooperative, was among the most gifted of the many photographers drawn to Cuba. (A selection of his work can be seen in his book “Havana: The Revolutionary Moment.” Also highly recommended is “Fidel’s Cuba: A Revolution in Pictures,” by Osvaldo Salas and Roberto Salas.) He borrowed money from Clay Felker, his roommate, to hire a charter flight to Havana the moment he learned Batista had fled the country after a lavish 1958 New Year’s Eve party. Glinn, like fellow photojournalist Lee Lockwood of the Black Star photo agency, knew that nothing is more seductive than making history except, perhaps, taking pictures of it. Glinn’s and Lockwood’s pictures show Castro and his men, weary with fatigue and near-disbelief stamped on their youthful faces, being met by a thronging populace beside itself with ardor, as they rolled through province after province, city after city, en route to the nation’s capital to proclaim their mastery of the island. Eyes dance with hope; the radiant future beckons.