In a “rapidly urbanizing world,” the poorest mothers and children living in urban centers—in developing countries and Western nations alike—face similar obstacles and high risk of death, a new report by Save the Children has found.

State of the World’s Mothers: The Urban Disadvantage, published Monday, details the hardships faced by impoverished families living in urban areas around the globe that have contributed to a growing survival gap between the world’s rich and poor.

“Our report reveals a devastating child survival divide between the haves and have-nots, telling a tale of two cities among urban communities around the world, including the United States,” Save the Children president and CEO Carolyn Miles said while announcing the findings.

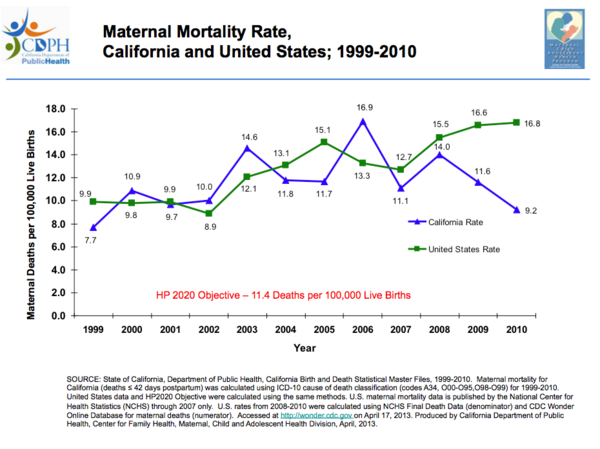

The U.S. ranked the worst among all developed nations for maternal risk of death.

Using five indicators, the annual report also indexes the best and worst countries for mothers, ranking 172 nations on maternal health, children’s well-being, educational status, economic status, and women’s political status.

The U.S. fell two slots from last year’s index, dropping from 31st to 33rd in the world. It also performed poorly on political representation, ranking 89th overall with a total 19.5 percent of national government seats being held by women.

Further, “[a]mong capital cities in high-income countries, Washington, D.C. has the highest infant death risk and great inequality,” the report states. What’s more, that rate—which is three times higher than those in Stockholm or Tokyo—is at an all-time low for the district.

To give an example of the wealth gap, babies in Ward 8, a neighborhood in D.C.’s Southeast quadrant, “where over half of all children live in poverty, are about 10 times as likely as babies in Ward 3, the richest part of the city, to die before their first birthday.”

High child death rates in slums in nations’ capitals are rooted in “disadvantage, deprivation, and discrimination,” Save the Children’s report states. “While high-quality private sector health facilities are more plentiful in urban areas, the urban poor often lack the ability to pay for this care—and may face discrimination or even abuse when seeking care.”