Smile at the customer. Bake cookies for your colleagues. Sing your subordinates’ praises. Share credit. Listen. Empathize. Don’t drive the last dollar out of a deal. Leave the last doughnut for someone else.

Sneer at the customer. Keep your colleagues on edge. Claim credit. Speak first. Put your feet on the table. Withhold approval. Instill fear. Interrupt. Ask for more. And by all means, take that last doughnut. You deserve it.

Of all the issues that preoccupy the modern mind—Nature or nurture? Is there life in outer space? Why can’t America field a decent soccer team?—it’s hard to think of one that has attracted so much water-cooler philosophizing yet so little scientific inquiry. Does it pay to be nice? Or is there an advantage to being a jerk?

We have some well-worn aphorisms to steer us one way or the other, courtesy of Machiavelli (“It is far better to be feared than loved”), Dale Carnegie (“Begin with praise and honest appreciation”), and Leo Durocher (who may or may not have actually said “Nice guys finish last”). More recently, books like The Power of Nice and The Upside of Your Dark Side have continued in the same vein: long on certainty, short on proof.

So it was a breath of fresh air when, in 2013, there appeared a book that brought data into the debate. The author, Adam Grant, is a 33-year-old Wharton professor, and his best-selling book, Give and Take: Why Helping Others Drives Our Success, offers evidence that “givers”—people who share their time, contacts, or know-how without expectation of payback—dominate the top of their fields. “This pattern holds up across the board,” Grant wrote—from engineers in California to salespeople in North Carolina to medical students in Belgium. Salted with anecdotes of selfless acts that, following a Horatio Alger plot, just happen to have been repaid with personal advancement, the book appears to have swung the tide of business opinion toward the happier, nice-guys-finish-first scenario.

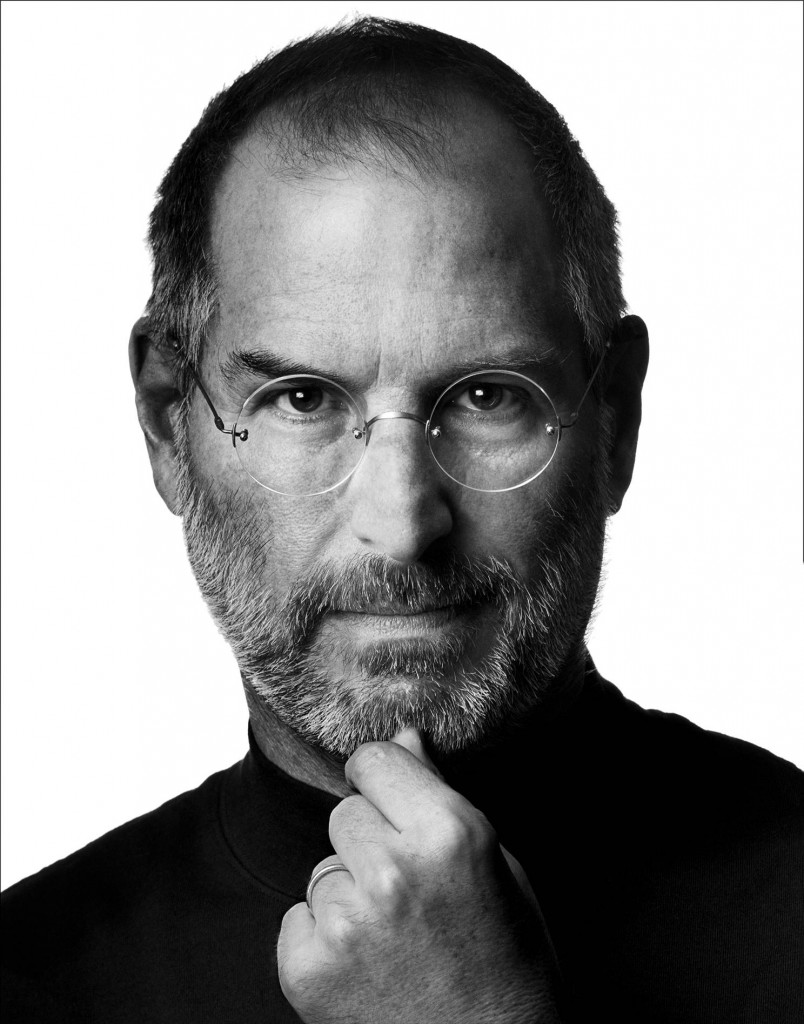

And yet suspicions to the contrary remain—fueled, in part, by another book: Steve Jobs, by Walter Isaacson. The average business reader, worried Tom McNichol in an online article for The Atlantic soon after the book’s publication, might come away thinking: “See! Steve Jobs was an asshole and he was one of the most successful businessmen on the planet. Maybe if I become an even bigger asshole I’ll be successful like Steve.”